Robotics for inclusive education

What is the Ride Robotics project about?

Brigitta Miksztai-Réthey: The programme teaches situations of real-life problems and methods for solving them: planning, teamwork, prioritization, social skills. It is like a simplified version of a project management curriculum written for children. In the case of children with special educational needs, the focus was on attention deficit, hyperactivity, reading disorder and high-functioning autism spectrum disorder.

When the Erasmus+ call for applications was posted, it was clear that we would apply. A consortium of four countries and seven organizations was established for the project, led by the Abacusan Studio, with the participation of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano and Interonline Cooperacion 2001 (Artec's partner in Spain), in addition to ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education. Four schools were involved in the testing, two from Hungary, one from Romania and one from Italy.

Brigitta Miksztai-Réthey, Lecturer at the Institute for the Psychology of Special Needs, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education

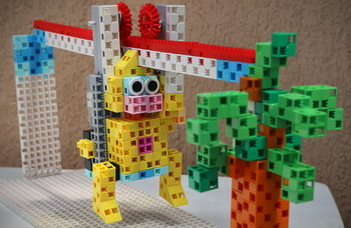

In the official project "Robotics for the Inclusive Development of Atypical and Typical Children", we use Artec robots. This system is similar to LEGO, except that the building blocks have no top and bottom and can be rotated in any direction. Therefore, this product gives greater freedom and develops the spatial-visual and logical skills of the children.

Katalin Mohai: In total, the project will entail ten curricula and ten modules. Each participating country could bring a story from their culture, for example, the Romanian folk tale "Five loaves of bread" and a couple of scenes from the Hungarian story, "The Boys of Paul Street" ("Pál utcai fiúk"). The development starts with the children directing their play based on the text with guided help. Afterwards, they will create a poster, video or presentation about their play, not only to develop their digital skills but also to share their work, so they can learn or take ideas from each other, and learn about the others’ cultures.

BMR: We have developed modules based on group work to develop different skills of the children involved. In robotics, we have also divided the tasks into several levels, from those involving only mechanical construction to those involving the construction of complex robots, even using partial artificial intelligence.

Csilla Kálózi-Szabó: The children have to act out a scene from a story, such as building a scene out of matchboxes. The developmental exercises gradually incorporate elements of robotics, and towards the end, the children build robots at different levels of development according to their abilities.

BMR: At the simplest level, in The Boys of Paul Street’s marble scene, all they have to do is build a ramp for the marbles to roll down on. At a higher level, they have to build a bullet gun, or a robot that can "shoot" a bullet if it gets close enough.

KM: The next stage is social skills, where the children have to divide roles and work together in groups. Because the children decide what to end the project with, learning becomes self-regulated, they don't feel like anything is imposed on them. The activities are linked to the different elements of the NAT, they can be integrated into a literature lesson or used in workshops. Inclusion is a key objective, group sessions bring together children with typical and atypical development, common goals and cooperative work allow for true inclusion, i.e. co-education. The differentiating methodology benefits both typical and SNI pupils and, last but not least, it sensitizes atypical children to the problems of SNI pupils. This has a very positive social impact in the long term.

Katalin Mohai, Assistant Professor, Lecturer at the Institute for the Psychology of Special Needs, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education

BMR: During the test phase at the participating school in Szeged, they found that children with atypical development could participate in group activities with children with typical development without any problems. Most difficulties were caused by gifted children who are not used to cooperating with others. Thanks to the project, the tables were turned: this time, gifted children got a taste of what it feels like to be different.

What changes can this project bring to education?

KM: The project is a catalyst for a digital education reform. In the 21st century, why not use robotics for analyzing a literary text, for example? We have identified 9 areas of skills in total (spatial orientation, social competences, computational thinking, creativity, etc.) and the teacher can decide which skills to focus on in their group.

CsKSz: Of course, for this, the teachers have to know the children in the group well. Some of the modules are linked to different subjects (literature, physics, and biology). The possibility of working with robots is a great motivation for the children, which allows them to read longer texts that they would not read otherwise. In today's digital world, where reading is increasingly being sidelined,

these colorful and exciting activities can help in getting children interested in the work.

BMR: It's important to adapt teaching methods to children's needs, as they start using digital tools from the age of two. The pandemic had a positive effect: it threw teachers into the digital deep end. At Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education, "Introduction to the use of digital technologies in special needs education" („Bevezetés a digitális technológiák gyógypedagógiai használatába”) is a compulsory course for all first-year students, therefore, almost 400 future special needs teachers are introduced to modern methods every year.

How can schools that would like to join the programme in the future get the tools they need?

BMR: The Abacusan Studio has a kit which they can lend to schools (for a limited time period) that would like to participate in the programme but cannot purchase the robots due to financial or other constraints. Schools that are interested in joining the project should contact the consortium in spring, 2022. In the meantime, it is worth to attend the studio's teacher training sessions, where teachers can learn the basics of robotics. Fortunately, you don't need to be a computer scientist to learn the methodology, which can be taught to any special needs teacher through the training sessions and manuals.

How has the pandemic affected the project?

CsKSz: The project launched in 2019 and will end in spring, 2022, with two years for the preparation of teaching materials and one year for the testing period in schools. The plan was to develop two curricula in advance, test them in schools and create the remaining modules based on the experience and feedback. This process was interrupted by the pandemic in spring, 2020, just as the broader testing was about to start.

Csilla Kálózi-Szabó, Assistant Professor, Lecturer at the Institute for the Psychology of Special Needs, ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education

BMR: The studio was planning summer camps last year, and a trial period for children with mild disabilities and trauma was planned with Bethesda Children's Hospital as well, but these to be cancelled due to the pandemic. There are many traumatized children or children who contracted COVID who have lost fine motor skills during the pandemic, and we wanted to organize robotics-based activities and camps for them.

Beyond participation, what is the role of ELTE Bárczi Gusztáv Faculty of Special Needs Education in this project?

KM: In order to measure the results, we are conducting an evaluation, testing certain skills before the start and after the end of the project, using psychological and pedagogical tests. We will also assess the children's skills before and after the project at the schools participating in the project. By comparing the two results, we will be able to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the project.

BMR: We have also involved the special education students from the Faculty in the project, for example, they can try out these methods in the context of computer-based learning support. We have also created methodological guides for the teachers in participating schools. These can be downloaded from our website, free of charge.

What are some memories you have made while working together?

KM: The children knew in advance that they were coming to a robotics workshop, they came in with sparkling eyes and were very enthusiastic. This is much closer to their world than a traditional class, here the teacher has more of a coordinator, moderator role.

BMR: What we have found is that these methods can be useful not only for children with mild disabilities

but also for children with severe disabilities.

In my work, I created a robotic vehicle for severely disabled children that stopped when the child put his / her hand in front of it. My physiotherapist colleagues and I observed that this had a huge motivational power: during exercises with such a robot, the child tries to coordinate his / her movements much better than in traditional physiotherapy. For children with severe intellectual disabilities, a simplified text comprehension module is very effective, in which the children have to reconstruct the text read to them using diagrams and pictorial symbols. Four of our students at the Faculty have participated in such exercises.

CsKSz: It would be great if we could go back to teaching in person as robotics cannot be taught through distance education. All of the representatives of the four countries, could only meet once in person, after which we could only continue our work online. Simplifying the administration and making it more flexible would certainly help a lot.